The Future of Epic Blizzards in a Warming World

What does global warming mean for extreme snowfall?

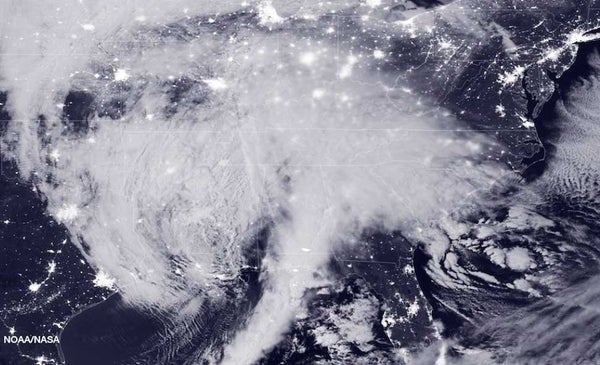

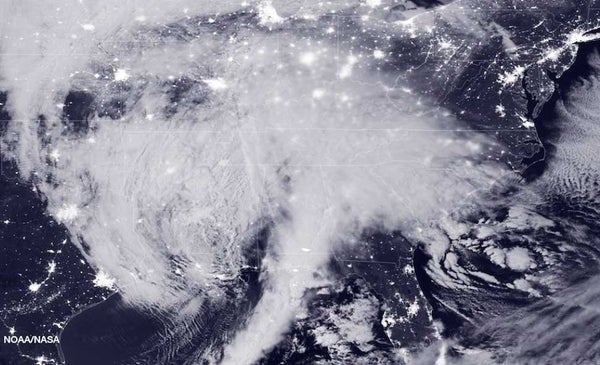

In case you haven’t heard, Washington, D.C., and other parts of the Mid-Atlantic region, are about to get walloped by a major storm that could bury the city in a record-breaking amount of snow.

The storm is expected to bring snows that could top 2 feet in the D.C. area and has already resulted in thousands of cancelled flights. While snows may not be quite as impressive further north, the storm’s fierce winds could whip up significant coastal flooding.

Part of the reason this Snowzilla storm is expected to dump so much snow is because it is pulling abundant moisture. As the planet warms because of excess heat trapped by human-emitted greenhouse gases, the atmosphere can hold more moisture. Scientists already expect heavy downpours to increase because of that. But there’s been little research into what that means for “epic blizzards” like this one.

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

It might seem that more moisture in the atmosphere along with warming temperatures should mean more rain than snow, and that’s true. But, it turns out, that’s only part of the story.

On Thursday, MIT climate researcher Paul O’Gorman reviewed a 2014 study he conducted that is one of the few to look at extreme snowfalls and warming. Speaking before a group of scientists during a talk at Columbia University, he detailed his use of climate models to look at how extreme snowfalls might change as the planet heats up. Global temperatures have already risen by nearly 2°F (1°C) since the late 1800s.

O’Gorman found that while both average annual snow amounts and extreme snowfalls would decline as temperatures rose, the extremes didn’t drop off as rapidly. Effectively, extreme snowfalls would become a bigger proportion of all snow events.

The reason for this disparity, O’Gorman found, has to do with the very particular temperature conditions in which extreme snows occur, sort of like a frozen version of the Goldilocks tale: If it’s too warm, you get rain, not snow, but if it’s too cold, there won’t be enough moisture in the air to fuel a full-on blizzard.

But looking across a winter, snows in general will occur across a wider band of temperatures—essentially, less warming is needed to chip away at the temperatures that produce all snow than the narrow band where extreme snows occur.

One possible exception to this decrease could be in very cold places, such as the Canadian Arctic, where even with warming it would still be cold enough to snow, but the temperature increase would mean more moisture to fuel that snow.

O’Gorman’s study is one of very few to look at the issue of warming and extreme snowfalls, and, to date, the pattern he identified has yet to be seen in snowfall observations, he said. He suspects this is because there are fewer snow observations than those for rain because snow happens over a much smaller area of Earth’s land surface.

“I don’t expect the signal on snowfall to emerge for another 20 years or so,” O’Gorman said.

That study also only looks at one specific aspect of snowstorms. Another relatively unexplored factor is how warming might influence the storms, called extratropical cyclones, that actually bring the snow as they sweep across the country. Some research has suggested that, like hurricanes, these systems could become less frequent, but those that do occur will be more intense, but it’s still an active area of research.

Discerning any role of warming in fueling this specific storm would require a specific attribution study, but one expected impact of this storm that does have a clear connection to climate change is the coastal flooding it could bring to areas from Maryland up to Long Island. As sea levels continue to rise from global warming, nor’easters and other intense storms are more likely to cause damaging floods.

But for a better picture of what the Snowpocalypses of the future might look like, much more research remains to be done.

This article is reproduced with permission from Climate Central. The article was first published on January 22, 2016.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor covering the environment, energy and earth sciences. She has been covering these issues for 16 years. Prior to joining Scientific American, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered earth science and the environment. She has moderated panels, including as part of the United Nations Sustainable Development Media Zone, and appeared in radio and television interviews on major networks. She holds a graduate degree in science, health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a B.S. and an M.S. in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.